There are few sights in cricket as mesmerizing as a ball that seems to defy physics. A fast bowler runs in, releases the ball on a straight path, and just as the batsman prepares to play it, the ball deviates sharply in the air, leaving them beaten all ends up. This is the art of swing bowling—a magical and mysterious skill that has baffled batsmen for over a century. But this “magic” is actually a fascinating application of aerodynamic principles.

This post will peel back the curtain on the science of swing bowling. We will explore the physics that makes a cricket ball move in the air, break down the techniques behind both conventional and reverse swing, and celebrate the legendary bowlers who turned this science into an art form.

The Physics of Swing: A Tale of Two Sides

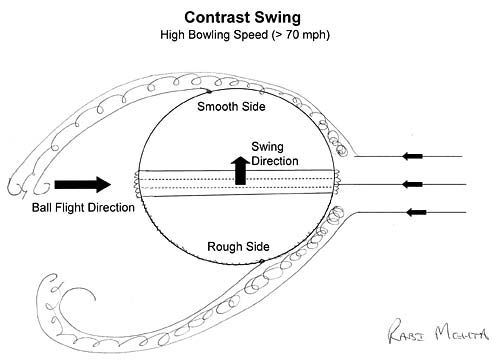

At its core, swing bowling is about creating a pressure difference on opposite sides of the cricket ball as it travels through the air. The key to this is the ball’s prominent seam and its condition.

A new cricket ball has two hemispheres of leather joined by a stitched seam that is raised slightly from the surface. To generate conventional swing, a bowler holds the ball with the seam angled towards the direction they want the ball to move (e.g., angled towards the slips for an outswinger to a right-handed batsman).

As the ball moves through the air, the airflow on each side behaves differently.

- The Shiny Side (Laminar Flow): The side of the ball without the seam is kept smooth and shiny by the fielding team. Air flows smoothly and quickly over this surface. This is known as “laminar flow.” The air “separates” from the ball’s surface relatively early.

- The Seam Side (Turbulent Flow): On the side with the angled seam, the stitches disrupt the air, creating a chaotic, churning layer of air. This is called “turbulent flow.” This turbulent layer of air “clings” to the ball for longer before separating from its surface.

This difference in separation points creates a pressure imbalance. The turbulent air on the seam side deflects the airflow, and according to Newton’s Third Law, the ball is pushed in the opposite direction. Therefore, the ball swings away from the turbulent side and towards the smooth, shiny side. So, if the shiny side is pointing towards the batsman’s leg side, the ball will swing in that direction (inswing).

Conventional Swing: The Bowler’s Craft

Generating conventional swing requires more than just holding the seam correctly. It’s a craft that involves meticulous care of the ball and a highly refined bowling action.

The Role of the Fielding Team

The process starts with the entire team. To maintain the conditions for swing, the fielding side works together to keep one side of the ball as smooth and dry as possible. You will often see players vigorously polishing one side of the ball on their trousers while ensuring the other side remains untouched. This contrast between a very smooth side and a rougher side enhances the pressure difference and promotes swing.

The Bowler’s Technique

The bowler’s action is crucial. A clean, repeatable release with a straight wrist and an upright seam is essential. The ball must be released with backspin, like a wheel rolling forward, to keep the seam stable in its angled position. If the seam wobbles, the aerodynamic effects are lost, and the ball will not swing.

Atmospheric conditions also play a significant role. Swing bowling is most effective in humid or overcast conditions. The moisture in the air is denser, which amplifies the aerodynamic effects on the ball, leading to more pronounced swing. This is why English conditions are famously conducive to swing bowling.

Reverse Swing: The Dark Art

As a cricket ball gets older, its surface becomes scuffed and worn. The once-shiny side loses its smoothness, and conventional swing begins to fade. This is when a mysterious and often more dangerous phenomenon can occur: reverse swing.

Flipping the Physics

Reverse swing happens when the ball becomes very old and rough, typically after 40-50 overs. The fielding team works to make one side exceptionally rough and dry while keeping the other side as smooth as possible, though it will still be scuffed.

With reverse swing, the roles of the smooth and rough sides are flipped. The “rougher” side becomes so abrasive that it trips the air into a turbulent flow very early. The “smoother” (but still worn) side now experiences laminar flow for longer. As a result, the pressure dynamics are inverted. The ball now swings towards the rough side and away from the smoother side.

This is what makes reverse swing so deceptive. A bowler will hold the ball with the same grip for an outswinger, but because the ball is reversing, it will swing back in towards the batsman. It moves late and often with greater speed than conventional swing, making it incredibly difficult to play. The art was pioneered and perfected by Pakistani bowlers in the 1980s and 90s.

The Masters of Swing

Throughout cricket history, certain bowlers have mastered this science and turned it into devastating art.

Wasim Akram (Pakistan)

Many consider Wasim Akram to be the greatest left-arm fast bowler of all time, and his mastery of swing, particularly reverse swing, was a key reason. Akram could swing the ball both ways at high pace with a new or old ball. His ability to hide the ball in his run-up and release it from an unusual angle made it almost impossible for batsmen to pick which way it would move. His spells of reverse swing in the 1992 World Cup final are legendary, where he produced two unplayable deliveries to dismiss Allan Lamb and Chris Lewis, effectively winning the cup for Pakistan.

James Anderson (England)

James Anderson is the most prolific swing bowler in the history of Test cricket. He is the ultimate craftsman of conventional swing. With a flawless, repeatable action and an unmatched ability to control the seam position, Anderson has tormented batsmen for nearly two decades. His mastery of the outswinger to the right-handed batsman is a thing of beauty. He holds the record for the most Test wickets by any fast bowler, a testament to his incredible skill and longevity, built on the foundation of swing.

Dale Steyn (South Africa)

Dale Steyn combined raw pace with lethal outswing, making him one of the most fearsome bowlers of the modern era. While many swing bowlers operate at a medium-fast pace, Steyn could generate significant swing while bowling consistently above 145 km/h (90 mph). His aggressive, high-energy approach and his ability to get the ball to swing late away from the right-hander made him a nightmare to face, especially with the new ball. His iconic, wild-eyed celebration after taking a wicket perfectly captured the intensity he brought to the art.

Conclusion: Science Meets Artistry

Swing bowling is the perfect embodiment of what makes cricket such a compelling sport. It is a deeply complex skill that relies on a precise understanding of physics, meticulous preparation, and flawless technical execution. Whether it’s the classical arc of a conventional outswinger or the late, wicked dip of a reverse-swinging yorker, the sight of a cricket ball moving through the air is pure theatre.

The next time you watch a fast bowler run in, pay close attention to the ball. Notice how the fielders care for it. Look at the bowler’s grip and the angle of the seam. You are witnessing a master applying the subtle laws of aerodynamics to deceive a batsman, turning science into a beautiful and destructive art form.